Death of a Newspaper-man: Analysis on The Lan Chengzhang Murder Case and the Related Ethical Issues of Chinese Journalism

Death of a Newspaper-man: Analysis on The Lan Chengzhang Murder Case and the Related Ethical Issues of Chinese Journalism

Author: Wang Pei

**Introduction **

It is said that being a Journalist is one of the most dangerous profession in the world. Until recently, this probably has not been true in modern China. According to an annual report published by the Paris-based ‘Reporters Without Borders’, in 2006, eighty-one journalists and thirty two media assistants were killed in 2006, among which only two are Chinese(RSF 2006). Compared with the fact that 4,746 Chinese miners died in underground explosions, fires and floods last year(Watts 2007), this is a rather small death toll. It is no wonder why the public was so shocked and puzzled, when the news that Lan Chengzhang, an employee of a Chinese newspaper, beaten to death by a coal mine owner and his gang, was reported by Chinese and international media. Even the president, Mr. Hu Jintao and other top leaders of China were paying attention to this case, according to the state news agency.

The aftermath of Lan’s death sparked hot debates both online and on the newspaper. Until now, in spite of that most of the suspects were arrested and the case has been in legitimate process, many facts still remain unclear. Is Mr. Lan a genuine reporter or a ‘false reporter’? Did Mr. Lan try to blackmail the mine owner or do a report? Should the local officials, who advocated ‘Crush False Reporter’ campaign, be responsible to some extent to Lan’s murder? What will the public regard the victim, a hero or a loser? This paper can not answer these questions due to their uncertainty.

However, this paper will review the Lan murder case and analyze the related ethical issues in Chinese journalism by answering the following questions: Who and to what extent were involved in Lan case? What kind of ethical issues rise from Mr. Lan’s death? Why these ethical issues are critical? How have these ethical issues been formed considering the broader context of Chinese journalism? And, more important, what kind of solutions can we propose to solve the ethical issues in order to avoid another victim?

Why the Lan Case?

The Lan Case is chosen with an attempt to analyze the ethical issues of Chinese journalism due to the following reason. Although Lan’s Murder is a individual case, it should not be considered as a normal criminal case. It reflects the deep conflict of the role of Chinese media. It discloses the long-existing relationships among local government, problematic businessmen, and the media. It focuses on the moral test and ethical dilemma of Chinese journalists. In short, the death of Lan is rooted deeply in the context, system and ethics of Chinese media.

The Lan Murdur Case

As the Lan Murder case is still in the legal process, many details are still clouded with doubts and controversies. The following story was based on the reports by CCTV (Wang 2007), the Guardian(Watts 2007), the Washington Post(Cody 2007) and other Chinese mainstream newspapers.

On the 10th January 2007, Lan Chengzhang, an employee of Zhongguo Maoyi Bao (China Trade News), visited to an apparently illegal coal mine near Datong, Shanxi province with two of his colleagues. He was heavily beaten by the illegal mine owner’s men and died the next day in hospital. The local authorities refused to regard Lan as a journalist because he did not have a press card(Cody 2007). Lan’s employer, Zhongguo Maoyi Bao, first claimed that Lan had not received any official permission to do the report(Cody 2007), then announced: “We certainly regarded him [Lan] as a journalist and we will do everything in our power to protect his rights,”’. Lan was also accused by the local authority that the purpose of his visit to the mine was to blackmail the mine owner rather than to do a report (Cody 2007). But this accusation was doubted and argued by Lan’s family and some intellectuals(Wang 2007).

It is needless to say that any possible accusation towards Mr. Lan can not be taken for granted. The question is: Why ‘being a false reporter’ and ‘practicing blackmail’ is such a convenient charge to Mr. Lan? To answer this question, we need to analyze the context of this particular case and think about the tough ethical issue.

The Context and the Ethical Issue: Blackmailing By Journalists In Datong

Nowadays blackmailing by journalists in China is not unusual. When a mine disaster happened, the catastrophe sometimes would draw ‘reporters and others pretending to be reporters who asked for “shut-up fees”’(Cody 2007). The mine owners who are responsible for the ‘accident’ and local officials who have interest in the mine business will buy silence from these ‘watch dogs’ to cover up the disaster from the eyes of the public. It is reported that Datong where the Lan case happened, false reporters and blackmailing have been prevailing since 2000. About 80 newspapers established reporter offices and nearly 600-1000 people claimed to be reporters there. However, Only 8 reporter offices with less than 50 employees are approved officially, as reported by Xin Jing Bao (the Beijing News)(2007).

Several reasons attribute to this ‘chaos’. First, many illegal mines are operated under the tolerance and protection of local officials and mine disasters happened frequently in Datong in these years. Second, since the illegal mine owners fear their illegal practices are disclosed, some reporter offices of newspapers hire many salesmen whose major duty is to persuade the illegal mine owners to buy silence in the name of advertisement, circulation or donation. And these salesmen usually get non-official press cards from their employers and act as reporters. Third, some people who are not hired by any real newspaper, find it a prosperous ‘business’, therefore, pretend to be reporters and start to blackmail the illegal miners and corrupted officials.

The local government was furious with this extortion and blackmailing-like practice. In stead of punishing the illegal miners, they decided to take action against the counterparts. They organized a campaign called “Crush down False Newspapers, False Magazines and False Reporters.” According to the official report released in January 2007, 36 ‘false reporters’ was caught during this campaign.

That is the background in which Mr. Lan was killed. Mr. Lan, as stated by the boss of his employer, was hired a week prior his death and still in his trail period. His title is ‘director of special issue department’, as shown on his employer-issued press card(Wang 2007). It can neither be concluded that he was one of the salesmen, nor the local campaigns lead to his death directly. However, knowing the context of blackmailing can help us to understand why so many disputes sparked and why the ethical issues are concerned in this case.

More Ethical Issues behind Blackmailing by Journalists

Although, blackmailing by journalists is not rare, it is not an isolated ethical issue. Indeed, extortion is related with other ethical issues and deeply rooted in the system of Chinese Media.

Many observers have noted the widespread corruption in Chinese journalism(Chengju 2000). The obvious corruption of journalists is accepting ‘gift money’ or ‘pocket money’. Another general practice of Chinese journalists is accepting freebies including gifts (Mp3 player, books etc.), free tickets, free trips, which is also practiced by some of their Western counterparts according to Keeble (Keeble 2001).

Some scholars attributed these problems to the fact that in general the Chinese journalists receive comparatively low wages(Yu 1997). So, these ‘gift money’ and freebies could be recognized as grease money which enables journalists to be better off. Most Chinese media tolerate these practice due to the tradition that a Chinese department often secretly undertakes business by using public facilities so as to provide staff members extra cash income or material benefits, argued by Chengju (Chengju 2000).

However, these scholars might miss the significant point that the media bodies practice corruption themselves. As argued by Zhao, in Chinese journalism, corruption ‘is not just a few individuals but an institutional and occupational phenomenon involving the majority of journalists and the majority of media organizations from the smallest to the very pinnacle of the Party’s propaganda apparatus(Zhao 1998).’

Actually, it is not rare for Chinese media institutions use commissions to bribe individuals who are in charge of buying advertisement and circulation. Apart from that, the media institutions encourage their journalists to involve in sales of advertisement and circulation.

How could this corruptive practice become blackmailing? In China, the media have powerful influence over moral issues, as discovered by Hua (Hua 2000). For some business operating immorally or illegally, disclosure of their malpractice on mass media will bring them crisis in public relations and finance. In order to cover up the truth, they often offer money to buy silence. Finding it a easy way to earn more money, the media usually hand the criticism report to the relevant business for confirmation. It is not blackmailing, the media assert, only for confirmation. However, as a game rule understood mutually, businessmen would rather pay ‘money for eliminating unluckiness ’(pocai xiaozai), as a Chinese proverb says. Thus, the blackmailing-like deal is done at last. These practices, as long as not done for self-interest, are seldom heavily punished by the authorities. An ‘internal criticism’ (neibu piping) and a ‘written regret letter’ (shumian jiantao) by the media leader to the authority is usually enough (Personal Interview, 30 January, 2007).

In order to squeeze the market, some newspapers establish reporter stations nationwide or province-wide. Newspapers claimed that the mission of these stations is to collect news, however, their main function is to collect money from companies. Last year, The State Administration for Press and Publications (SPPA) punished several newspapers who blackmail companies through their reporter stations(Yu 2007).

When the media practice corruption themselves, how could the public expect well behavior from journalists? According to a survey conducted in 1997(Yu 1997), about 66% of the surveyed journalists agree to sell advertisement for their employers. This consensus increases the posibility of touching the bottom line—blackmailing for one’s own benefit.

The Root of Ethical Issues in Chinese Journalism

As analyzed above, the ethical issues arise from Chinese journalism is personal and institutional. But the root of them is the media system, which changed significantly since late 1970s.

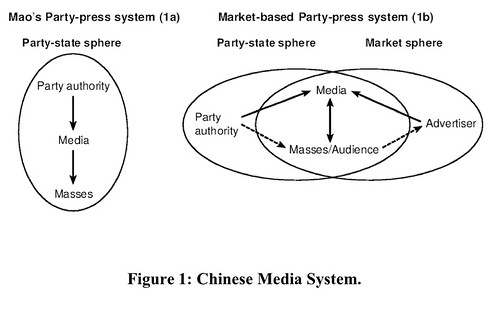

In the Maoist era, Chinese media were simply political organs for the use of propaganda and ‘mouthpiece’ of the Party. In the 1990s, the Party decided to severe media subsidies and push media to scramble for advertising revenues in the commercial sea(Chin-Chuan 2000). Or, as Zhao(Zhao 2004) argued, ‘China’s once state-subsidized and Party-controlled propaganda organs are rapidly transforming themselves into advertisement-based and market-driven capitalistic media enterprises under Party ownership…’ Since then, the Chinese media have served ‘two masters’, the Party and the masses. This can be better understood by figure 1 illustrated by Yong (Yong 2000).

Figure 1: Chinese Media System.

As shown on Figure 1, the dual compulsions of Party-state control and market imperative have significantly transformed the structure of the Chinese media. Being a ‘mouse piece’, media should take extreme cautions to keep ‘political safety’. This means that they must eliminate any reports conflicting with the Party’s interest and must propagandize the Party’s voice when needed. Any breach of these rules, would be regarded as a more serious misconduct, and would lead to serious consequence, from sacking the boss to closure.

As a result, Chinese media tend to stay away from politics and are disinclined to report domestic social conflicts. They rush to market, with profit motive as a driving force(Zhao 2004). However, since too many media competing in the underdeveloped market, the competition between media outlets affiliated with various Party state units is intense. This zero-sum game certainly created winners and losers. For the losers they have to struggle to survive by malpractice. Although the winners seldom use blackmailing, they sometimes use bribery to sustain their market share.

How about the journalists? Most of them practically cooperate with their employers, obey the Party and favor their advertisers. Some argued that their increased economic and social isolation from the low classes and their increased materialism are likely to make them a ‘silent partner’ (Zhao 2004). It is incorrect to deny courageous and virtuous journalists exist in China. In fact, some journalists use blogs to express their true feeling and tell the truth. The murder of Mr. Lan was first reported in Tianya site using a fake name, which was believed to belong to an anonymous reporter.

How to Resolve the Ethical Issue?

The ethical issues severely damage the image of media and reduce their accountability. The hot debates about the Lan case, on one hand is pouring fury towards illegal businessmen, on the other hand is expressing discontent with the media. To solve these ethical problems is nonetheless easy.

Some believe codes of ethics and codes of conduct would help because ‘a code may be a way of giving moral support to journalists who have been victimized, and of encouraging solidarity within the profession(Harris 1992).’

In 1997, the Professional Code of Ethics for Chinese Journalists was enforced in China. As stipulated in this code, journalists are forbidden to accept ‘gift money’ and freebies. Moreover, reporters should never involve in any business activities like selling advertisement. However, study found that this code had done little to improve the journalistic ethics(Yu 1997). The ineffectiveness of this code not only attributes to the root of media system, as discussed above, but also to the code itself. This code does say anything about enforcement. As Harris argued, ‘If breaches go unpunished…, then what protection will the public gain from the existence of the code?(Harris 1992) ’

Some media outlets might think that the Code was too unrealistic. So they made their own practical codes. Chengdu Business News (CBN) took four anti-corruption rules. First, separating the newsroom from the business units to prevent journalists from making own benefits. Second, separating editing and reporting to curb the coverage of paid articles. Third, stipulating reward and punishment rules to enforce the code. Finally and interestingly, ‘All gift money received by journalists from interviewees must be turned over to the newspaper’s financial office. Forty percent of gift money, however, will be returned to relevant journalists later…(Chengju 2000)’

These codes were proved more effective than the official one(Chengju 2000). However, someone may argue that these anti-corruption rules are not hard to play trick with, as a Chinese saying warns, ‘When angel grows one inch, Devil grows one foot (Daogao yichi, mogao yizhang).’

The real problem of these codes is, some of them are against morality. If getting gift money is acceptable, what the public would view the media? Indeed, nowadays most of the media have separated journalism and business, but how could they restrain their journalists from business activity, while their competitors have emptied the newsroom to visit the potential clients?

The remedy might lie in legislation because it is believed that ‘…the provision of the blunt instrument of a specific law is to establish bodies legally empowered to regulate the media(Sanders 2003).’ Unfortunately, China has no press law. If there were one press law, the rights of journalists and media employees including Mr. Lan would have been protected and the misconducts would be restricted. Interestingly, in 1999, the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences Working Party on Media Law Reform had spent a month at Nottingham Trent University to study English approaches to media law. They urged the need for “a national press law to protect the news media from abuse from the executive and the Party”(De Burgh 2000). After seven years, media law is still not on the legislation schedule.

Codes of conduct and media law can not solve ethical issues alone. By and large, ethics is a personal matter. For anyone who faces ethical questions, self-regulation and self-determination is the ultimate resolution. For Chinese journalists, maybe Bok’s model could be helpful. Bok recommends that any ethical questions should be analyzed in three steps. First, consult your own conscience about the ‘rightness’ of an action. Second, seek expert (living or dead) advice for advice to the act creating the ethical problems. Third, if possible, conduct a public discussion with the parties involved in the dispute(Patterson and Wilkins 1998). However, this model is not absolute.

Some Conclusion Words

Although the Lan Case seems like an accident, this kind of tragedy is almost inevitable. The media, on one hand, are strictly controlled by the Party and state, on the other hand, they have been pushed into the commercial world since the reform in 1990s. Immoral and even illegal practices are not uncommon in Chinese journalisms. The journalists and employees of Chinese media, are under pressure from the Party, the market, the mass and their employers. The lack of protection of media law jeopardizes their situation. They are generally treated as a mean instead of an end. Although this situation cannot justify immoral or illegal individual behavior, it seems unfair to blame journalists alone for all the ethical problems. To solve these ethical issues, a realistic code of conducts, a media law and individual self-regulation seems equally important.

Lan Chengzhang’s death has enabled a lot of Chinese to see the dark side of the media system and society. Thus, the bottle of secrets has been opened. Currently, hot debates concerning social justice, media reforms and journalistic ethics are still underway. On Netease, a Chinese news portal, the majority of internet users are condemning the murderers and the disheartened officials, and appealing for more journalists to meet the public’s expectation by chasing truth and justice. Although the Lan case is still waiting for a trial. All believe that Lan should not die in vain.

Wang Keqin, a courageous journalist, who has received death thread for several times, wrote a series of report about Lan’s death. On his blog, he posted a photograph of Lan’s daughter. Holding his father’s portrait, the little girl lifted her misty eyes. What is ethics? Why we need ethics? How can a Chinese journalist do something to improve his ethics? The little girl’s eyes have explained all.

Reference

(2007). Shanxi Datong ‘Jia Jizhe’ Luanxiang (The Chaos of ‘False Reporters’ in Datong, Shanxi). Xin Jing Bao (The Beijing News). Beijing. Chengju, H. (2000). “The Development of a Semi-Independent Press in Post-Mao China: An overview and a case study of Chengdu Business News.” Journalism Studies 1: 649-664. Chin-Chuan, L. (2000). “China’s Journalism: the emancipatory potential of social theory.” Journalism Studies 1: 559-575. Cody, E. (2007). Blackmailing By Journalists In China Seen As ‘Frequent’. Washington Post Foreign Service. Washington: A01. Cody, E. (2007). Fatal Beating Victim: Journalist or Fraud? Washington Post Foreign Service. Washington: A21. De Burgh, H. (2000). “Chinese Journalism and the Academy: the politics and pedagogy of the media.” Journalism Studies 1: 549-558. Harris, N. (1992). Codes of Conduct for Journalists. Ethical issues in journalism and the media / edited by Andrew Belsey and Ruth Chadwick. A. Belsey and R. F. Chadwick. London, Routledge: 62-76. Hua, X. (2000). “Morality Discourse in the Marketplace: narratives in the Chinese television news magazine Oriental Horizon.” Journalism Studies 1: 637-647. Keeble, R. (2001). Ethics for journalists / by Richard Keeble, Routledge. Patterson, P. and L. Wilkins (1998). Media ethics : issues and cases / Philip Patterson and Lee Wilkins, Wm. C. Brown. RSF (2006). Press Freedom in 2006. Paris, Reporters Without Borders: 1-8. Sanders, K. (2003). Ethics and journalism / Karen Sanders, SAGE. Wang, L. (2007) “Lan Chengzhang: The Accidental Death of a “Reporter.”” Volume, DOI: Watts, J. (2007). Chinese reporter’s murder sparks public debate. The Guardian. Yong, Z. (2000). “From Masses to Audience: changing media ideologies and practices in reform China.” Journalism Studies 1: 617-635. Yu, G. (1997). Woguo Xinwen Gongzuozhe Zhiye Yishi yu Zhiye Daode Chouyang Diaocha Zongti Baogao (A Survey on Professional Awareness and Professional Ethics of Chinese Journalists). Beijing, Journalism Research Center of China. Yu, X. (2007). Lan Chengzhang Zhi Si Ying Chengwei Baoye Gaige Zhi Qiji (The Death of Lan Chengzhang Should be an Opportuty of Newspaper Reform). China Yougth Daily. Beijing. Zhao, Y. (1998). Media, market and democracy in China : between the party line and the bottom line / Yuezhi Zhao, Illinois U. P. Zhao, Y. (2004). The State, the Market, and Media Control in China. Who Owns the Media: Global Trends and Local Resistance. P. Thomas and Z. Nain. Penang, Malaysia, Southbound Press and London: Zed Books: 179-212.

©️ All rights reserved. 📧 [email protected]